If you ask them which companies they admire, people quickly point to organizations like General Electric, Starbucks, Nordstrom, or Microsoft. Ask how many layers of management these companies have, though, or how they set strategy, and you’ll discover that few know or care. What people respect about the companies is not how they are structured or their specific approaches to management, but their capabilities—an ability to innovate, for example, or to respond to changing customer needs. Such organizational capabilities , as we call them, are key intangible assets. You can’t see or touch them, yet they can make all the difference in the world when it comes to market value.

These capabilities—the collective skills, abilities, and expertise of an organization—are the outcome of investments in staffing, training, compensation, communication, and other human resources areas. They represent the ways that people and resources are brought together to accomplish work. They form the identity and personality of the organization by defining what it is good at doing and, in the end, what it is . They are stable over time and more difficult for competitors to copy than capital market access, product strategy, or technology. They aren’t easy to measure, so managers often pay far less attention to them than to tangible investments like plants and equipment, but these capabilities give investors confidence in future earnings. Differences in intangible assets explain why, for example, upstart airline JetBlue’s market valuation is twice as high as Delta’s, despite JetBlue’s having significantly lower revenues and earnings.

In this article, we look at organizational capabilities and how leaders can evaluate them and build the ones needed to create intangible value. Through case examples, we explain how to do a capabilities audit, which provides a high-level picture of an organization’s strengths and areas for improvement. We’ve conducted and observed dozens of such analyses, and we’ve found the audit a powerful way to evaluate intangible assets and render them concrete and measurable.

Organizational Capabilities Explained

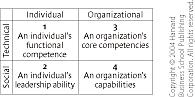

While people often use the words “ability,” “competence,” and “capability” interchangeably, we make some distinctions. In technical areas, we refer to an individual’s functional competence or to an organization’s core competencies; on social issues, we refer to an individual’s leadership ability or to an organization’s capabilities. With these differences in mind, let’s compare individual and organizational levels of analysis as well as technical and social skill sets:

In the table above, the individual-technical cell (1) represents a person’s functional competence, such as technical expertise in marketing, finance, or manufacturing. The individual-social cell (2) refers to a person’s leadership ability—for instance, to set direction, to communicate a vision, or to motivate people. The organizational-technical cell (3) comprises a company’s core technical competencies. For example, a financial services firm must know how to manage risk. The organizational-social cell (4) represents an organization’s underlying DNA, culture, and personality. These might include such capabilities as innovation and speed.

Organizational capabilities emerge when a company delivers on the combined competencies and abilities of its individuals. An employee may be technically literate or demonstrate leadership skill, but the company as a whole may or may not embody the same strengths. (If it does, employees who excel in these areas will likely be engaged; if not, they may be frustrated.) Additionally, organizational capabilities enable a company to turn its technical know-how into results. A core competence in marketing, for example, won’t add value if the organization isn’t able to spark change.

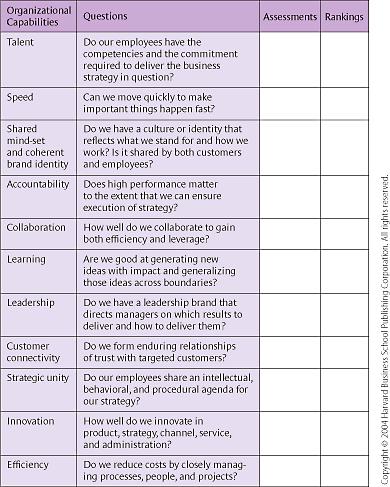

There is no magic list of capabilities appropriate to every organization. However, we’ve identified 11—listed below—that well-managed companies tend to have. (Such companies typically excel in as many as three of these areas while maintaining industry parity in the others.) When an organization falls below the norm in any of the 11 capabilities, dysfunction and competitive disadvantage will likely ensue.

Talent:

We are good at attracting, motivating, and retaining competent and committed people. Competent employees have the skills for today’s and tomorrow’s business requirements; committed employees deploy those skills regularly and predictably. Competence comes as leaders buy (acquire new talent), build (develop existing talent), borrow (access thought leaders through alliances or partnerships), bounce (remove poor performers), and bind (keep the best talent). Leaders can earn commitment from employees by ensuring that the ones who contribute more receive more of what matters to them. Means of assessing this organizational capability include productivity measures, retention statistics (though it’s a good sign when employees are targeted by search firms), employee surveys, and direct observation.

Speed:

We are good at making important changes rapidly. Speed refers to the organization’s ability to recognize opportunities and act quickly, whether to exploit new markets, create new products, establish new employee contracts, or implement new business processes. Speed may be tracked in a variety of ways: how long it takes to go from concept to commercialization, for example, or from the collection of customer data to changes in customer relations. Just as increases in inventory turns show that physical assets are well used, time savings demonstrate improvements in labor productivity as well as increased enthusiasm and responsiveness to opportunities. Leaders should consider creating a return-on-time-invested (ROTI) index, so they can monitor the time required for, and the value created by, various activities.

Shared Mind-Set and Coherent Brand Identity:

We are good at ensuring that employees and customers have positive and consistent images of and experiences with our organization. To gauge shared mind-set, ask each member of your team to answer the following question: What are the top three things we want to be known for in the future by our best customers? Measure the degree of consensus by calculating the percent of responses that match one of the three most commonly mentioned items. We have done this exercise hundreds of times, often to find a shared mind-set of 50% to 60%; leading companies score in the 80% to 90% range. The next step is to invite key customers to provide feedback on brand identity. The greater the degree of alignment between internal and external mind-sets, the greater the value of this capability.

Accountability:

We are good at obtaining high performance from employees. Performance accountability becomes an organizational capability when employees realize that failure to meet their goals would be unacceptable to the company. The way to track it is to examine the tools you use to manage performance. By looking at a performance appraisal form, can you derive the strategy of the business? What percent of employees receive an appraisal each year? How much does compensation vary based on employee performance? Some firms claim a pay-for-performance philosophy but give annual compensation increases that range from 3.5% to 4.5%. These companies aren’t paying for performance. We would suggest that with an average increase of 4%, an ideal range for acknowledging both low and high performance would be 0% to 12%.

Collaboration:

We are good at working across boundaries to ensure both efficiency and leverage. Collaboration occurs when an organization as a whole gains efficiencies of operation through the pooling of services or technologies, through economies of scale, or through the sharing of ideas and talent across boundaries. Sharing services, for example, has been found to produce a savings of 15% to 25% in administrative costs while maintaining acceptable levels of quality. Knowing that the average large company spends about $1,600 per employee per year on administration, you can calculate the probable cost savings of shared services. Collaboration may be tracked both throughout the organization and among teams. You can determine whether your organization is truly collaborative by calculating its breakup value. Estimate what each division of your company might be worth to a potential buyer, then add up these numbers and compare the total with your current market value. As a rule of thumb, if the breakup value is 25% more than the current market value of the assets, collaboration is not one of the company’s strengths.

Learning:

We are good at generating and generalizing ideas with impact. Organizations generate new ideas through benchmarking (that is, by looking at what other companies are doing), experimentation, competence acquisition (hiring or developing people with new skills and ideas), and continuous improvement. Such ideas are generalized when they move across a boundary of time (from one leader to the next), space (from one geographic location to another), or division (from one structural entity to another). For individuals, learning means letting go of old practices and adopting new ones.

Leadership:

We are good at embedding leaders throughout the organization. Companies that consistently produce effective leaders generally have a clear leadership brand—a common understanding of what leaders should know, be, and do. These companies’ leaders are easily distinguished from their competitors’. Former McKinsey employees, for instance, consistently approach strategy from a unique consulting perspective; they take pride in the number of the firm’s alumni who become CEOs of large companies. In October 2003, the Economist noted that 19 former GE stars immediately added an astonishing $24.5 billion (cumulatively) to the share prices of the companies that hired them. You can track your organization’s leadership brand by monitoring the pool of future leaders. How many backups do you have for your top 100 employees? In one company, the substitute-to-star ratio dropped from about 3:1 to about 0.7:1 (less than one qualified backup for each of the top 100 employees) after a restructuring and the elimination of certain development assignments. Seeing the damage to the company’s leadership bench, executives encouraged potential leaders to participate in temporary teams, cross-functional assignments, and action-based training activities, thus changing the organization’s substitute-to-star ratio to about 1:1.

Customer Connectivity:

We are good at building enduring relationships of trust with targeted customers. Since it’s frequently the case that 20% of customers account for 80% of profits, the ability to connect with targeted customers is a strength. Customer connectivity may come from dedicated account teams, databases that track preferences, or the involvement of customers in HR practices such as staffing, training, and compensation. When a large portion of the employee population has meaningful exposure to or interaction with customers, connectivity is enhanced. To monitor this capability, identify your key accounts and track the share of those important customers over time. Frequent customer-service surveys may also offer insight into how customers perceive your connectivity.

Strategic Unity:

We are good at articulating and sharing a strategic point of view. Strategic unity is created at three levels: intellectual, behavioral, and procedural. To monitor such unity at the intellectual level, make sure employees from top to bottom know what the strategy is and why it is important. You can reinforce this sort of shared understanding by repeating simple messages; you can measure it by noting how consistently employees respond when asked about the company’s strategy. To gauge strategic accord at the behavioral level, ask employees how much of their time is spent in support of the strategy and whether their suggestions for improvement are heard and acted on. When it comes to process, continually invest in procedures that are essential to your strategy. For example, Disney must pay constant attention to any practices relating to the customer-service experience; it must ensure that its amusement parks are always safe and clean and that guests can successfully get directions from any employee.

Innovation:

We are good at doing something new in both content and process. Innovation—whether in products, administrative processes, business strategies, channel strategies, geographic reach, brand identity, or customer service—focuses on the future rather than on past successes. It excites employees, delights customers, and builds confidence among investors. This capability may be tracked through a vitality index (for instance, one that records revenues or profits from products or services created in the last three years).

Efficiency:

We are good at managing costs. While it’s not possible to save your way to prosperity, leaders who fail to manage costs will not likely have the opportunity to grow the top line. Efficiency may be the easiest capability to track. Inventories, direct and indirect labor, capital employed, and costs of goods sold can all be viewed on balance sheets and income statements.

Conducting a Capabilities Audit

Just as a financial audit tracks cash flow and a 360-degree review assesses leadership behaviors, a capabilities audit can help you monitor your company’s intangible assets. It will highlight which ones are most important given the company’s history and strategy, measure how well the company delivers on these capabilities, and lead to an action plan for improvement. This exercise can work for an entire organization, a business unit, or a region. Indeed, any part of a company that has a strategy for producing financial or customer-related results can do an audit, as long as it has the backing of the leadership team. We’ll walk through the process below, describing as we go the experiences of two companies that recently performed such audits—Boston Scientific (a medical device manufacturer) and InterContinental Hotels Group—and what they did as a result of their findings.

The Massachusetts-based company Boston Scientific has enjoyed strong growth over the past 25 years. In particular, its international division delivers about 45% of company revenues and 55% of company profits. Yet in 2003, the group’s executives still wanted to find ways to improve on the division’s success, so Edward Northup, president of Boston Scientific International, decided to engage his leadership team in a capabilities audit.

The first step was to identify the areas that were critical in meeting the group’s goals. Using the 11 generic capabilities defined above as a starting point, leaders at Boston Scientific adapted the language to suit their business requirements. (No matter how you create the list, the capabilities you audit should reflect those needed to deliver on your company’s strategic promises.) Next, to evaluate the organization’s performance on these capabilities, the international division’s executives—along with their bosses and employees and a group of peer executives from other divisions—completed a short online survey. Adapted from the generic questionnaire shown in the exhibit “How to Perform a Capabilities Audit,” the survey comprised 20 questions, with space for comments. For each capability, respondents were asked to rate on a scale of one to five the group’s current performance as well as the level of achievement the division would need in order to meet its goals. This exercise showed gaps between current and desired capability. For example, on strategic unity—the extent to which employees understood and agreed upon strategy—the score for actual achievement was 0.91 points lower than the score for desired performance. Respondents also chose two capabilities that would most affect the group’s ability to deliver on its customer-related and financial promises.

The leaders discussed the survey findings at an off-site meeting. To address the strategic-unity gap, they developed a clearer statement of strategy that sharpened the group’s focus on service and profitability. Then, before forming an overall improvement plan, they defined the capabilities that would be most critical to executing that strategy. They didn’t necessarily choose capabilities with low scores in actual performance. For example, even though the group showed relative weakness in learning and innovation, the leadership team didn’t see those capabilities as essential to meeting group goals, because the division is primarily a sales, marketing, and distribution arm of the company. However, although the division scored high on talent (see the exhibit “Does the Talent Deliver?”), the leaders chose to invest in further developing this capability since it would be critical to success; in particular, they focused on strengthening marketing skills and building talent that would allow them to target a broader set of customers. They also launched an effort to create a leadership brand, starting with a new model of high performance. Finally, they began to assess bench strength in support of that leadership brand, starting with the organization’s three regional presidents.

The idea, in short, is not necessarily to boost weak capabilities but to identify and build capabilities that will have the strongest and most direct impact on the execution of strategy.

The Berkshire, England–based InterContinental Hotels Group (IHG) conducted its audit across the entire company. In late 2002 and early 2003, the global organization—recently spun off from Bass Group—faced bloated overhead costs in the competitive hotel industry, experienced a decline in business and vacation travel because of the worldwide economic downturn and the spread of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), underwent a brand name change (from Six Continents), and battled a hostile takeover attempt by British entrepreneur Hugh Osmond. Deutsche Bank analyst Mark Finnla, in a January 2003 report, described the hotels as “chronically underperforming…[and] making less than a third of what they should be.” In an effort to improve performance, chief executive Richard North initiated an “organization review.”

As at Boston Scientific International, the audit process started with collection of feedback from multiple sources—executives, employees at all levels, and franchisees who owned and managed individual hotels. The information was gathered by an organization-review design team made up of high-potential employees from all regions. Supported by external consultants, the team members worked on the review process full-time for several months before making recommendations to the IHG executive committee. Based on this review, efficiency, or reducing costs, quickly became a priority. The company’s costs were 15% to 20% higher than the industry average, and IHG swiftly took measures to streamline its operations among the various regions, creating a shared services center and aligning finance, human resources, and corporate functions.

IHG executives also looked at what capabilities would be essential for future success, assessing actual and desired capabilities in terms of where the company required world-class skill, where it needed to demonstrate industry superiority, and where it needed to achieve industry parity for optimal cost-efficiency. (For a visual breakdown of the areas examined, see the exhibit “A Snapshot of IHG’s Capabilities Audit Results.”) The capabilities under review supported the overarching priority of efficiency. Leaders decided, for example, that the company should achieve world-class performance in collaboration. As part of this strategic push, IHG gave up its decentralized structure, in which each region operated independently and was responsible for its own budget and operation, and became a unified corporate entity whose regions needed to work together to solve budget shortfalls, information technology challenges, and the like. By collaborating across regions and hotels, IHG streamlined operations and saved more than $100 million a year. By focusing on the gap between actual and desired capabilities, company leaders were able to determine where to invest leadership attention. This new focus allowed IHG to fend off the hostile takeover, demerge successfully, increase its share price by 71% from April 2003 to February 2004, and outperform the FTSE 100 by a factor of two, while reenergizing the company culture. A survey showed dramatic increases in employee morale and confidence in company leadership. The quality of management at the company is no longer a matter of public debate.

Lessons Learned

No two audits will look exactly the same, but our experience has shown us that, in general, there are good and bad ways to approach the process. You’ll be on the right track if you observe a few guidelines.

Get focused.

It’s better to excel at a few targeted capabilities than to diffuse leadership energy over many. Leaders should choose no more than three on which to spend their time and attention; they should aim to make at least two of them world-class. This means identifying which capabilities will have the most impact and will be easiest to implement, and prioritizing accordingly. (Boston Scientific chose talent, leadership, and speed. IHG zeroed in on collaboration and speed since the company’s leaders felt that working across boundaries faster would enable them to reach their strategic and financial goals.) The remaining capabilities identified in the audit should meet standards of industry parity. Investors seldom seek assurance that an organization is average or slightly above average in every area; rather, they want the organization to have a distinct identity that aligns with its strategy.

Recognize the interdependence of capabilities.

While you need to be focused, it’s important to understand that capabilities depend on one another. So even though you should target no more than three for primary attention, the most important ones often need to be combined. For example, speed won’t be enough on its own; you will likely need fast learning, fast innovation, or fast collaboration. As any capability improves, it will probably improve others in turn. We assume that no capabilities are built without leaders, so working on any one of them builds leadership. As the quality of leadership improves, talent and collaboration issues often surface—and in the process of resolving those problems, the company usually strengthens its accountability and learning.

Learn from the best.

Compare your organization with companies that have world-class performance in your target capabilities. Quite possibly, these companies won’t be in the same industry as your organization. It’s often helpful, therefore, to look for analogous industries where companies may have developed extraordinary strength in the capability you desire. For example, hotels and airlines have many differences, but they’re comparable when it comes to several driving forces: stretching capital assets, pleasing travelers, employing direct-service workers, and so on. The advantage of looking outside your own industry for models is that you can emulate them without competing with them. They’re far more likely than your top competitors to share insights with you.

Create a virtuous cycle of assessment and investment.

A rigorous assessment helps company executives figure out what capabilities will be required for success, so they can in turn decide where to invest. Over time, repetitions of the assessment-investment cycle result in a baseline that can be useful for benchmarking.

Compare capability perceptions.

Like 360-degree feedback in leadership assessments, capabilities audits sometimes reveal differing views of the organization. For example, employees or customers may not agree with top leaders’ perception that there is a shared mind-set. Involve stakeholders in improvement plans. If investors rank the firm low on various capabilities, for instance, the CEO or CFO might want to meet with the investors to discuss specific action plans for moving forward.

Match capability with delivery.

Leaders need to do more than talk about capability; they need to demonstrate it. Rhetoric shouldn’t exceed action. Expectations for improvement should be outlined in a detailed plan. One approach is to bring together leaders for a half-day session to generate questions for the plan to address: What measurable outcome do we want to accomplish with this capability? Who is responsible for delivering on it? How will we monitor our progress in attaining or boosting this capability? What decisions can we make immediately to foster improvement? What actions can we as leaders take to promote this capability? Such actions may include developing education or training programs, designing new systems for performance management, and implementing structural changes to house the needed capabilities. The best capability plans specify actions and results that will occur within a 90-day window. HR professionals may be the architects, but managers are responsible for executing these plans.

Avoid underinvestment in organization intangibles.

Often, leaders fall into the trap of focusing on what is easy to measure instead of what is in greatest need of repair. They read balance sheets that report earnings, EVA, or other economic data but miss the underlying organizational factors that may add value. At times the capability goals can be very concrete, as with IHG’s focus on efficiency.

Don’t confuse capabilities with activities.

An organizational capability emerges from a bundle of activities, not any single pursuit. So leadership training, for instance, needs to be understood in terms of the capability to which it contributes, not just the activity that takes place. Instead of asking what percent of leaders received 40 hours of training, ask what capabilities the leadership training created. To build speed, IHG leaders made changes in the company’s structure, budgeting processes, compensation system, and other management practices. Attending to capabilities helps leaders avoid looking for single, simple solutions to complex business problems. • • •

Few would dispute that intangible assets matter. But it can be quite difficult to measure them and even harder to communicate their value to stakeholders. An audit is a way of making capabilities visible and meaningful. It helps executives assess company strengths and weaknesses, assists senior leaders in defining strategy, supports midlevel managers in executing strategy, and enables frontline leaders to make things happen. And it helps customers, investors, and employees alike recognize the organization’s intangible value.

Post a Comment